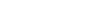

Ancestral Worship

2023-01-01

The Chinese nation has a long and rich tradition of ancestral worship, emphasizing filial piety, respect for the elderly, and the continuation of family virtues from generation to generation—heritage cherished since ancient times. Over the centuries, ancestral worship has been a resilient and enduring part of the Chinese cultural tradition, connecting regions, families, and individuals, becoming an essential link to the past and extending into the future.

Ancestral portraits, as symbolic representations of ancestral worship, serve as tangible carriers of family emotions, bearing rich historical and cultural traditions. Alongside ancestral veneration, family genealogies, and ancestral temple systems, ancestral portraits constitute the fundamental part of China's millennia-old ancestral system. They embody the practice of traditional ancestral worship, influencing various aspects of art, politics, and social relationships.

In the creation of ancestral portraits, meticulous attention is given to accurately depicting their facial features and attire, culminating in a comprehensive representation within Chinese figure painting. Since the Song and Yuan dynasties, as the aesthetic tastes of the literati class evolved, the traditional art of figure painting from the Han and Tang dynasties gradually became marginalized. However, due to its functional significance, ancestral portraits continued to develop, to some extent, preserving the residual veins of traditional figure painting. In the late Ming dynasty (1368-1644), beyond professional artists, the literati also participated in enriching the artistic styles and humanistic connotations of ancestral portraits.

The diverse, widespread, and numerous ancestral portraits contribute significantly to rectifying certain biases in previous art research. They facilitate a reassessment of the classification of art history, delineation of the scope of folk art, elimination of the binary opposition between folk painting and literati painting, and correction of assertions regarding the "decline of figure painting".

The Ming and Qing (1644-1911) ancestral portrait collection at the China National Academy of Arts is extensive in quantity and distinguished in quality. This exhibition, based on a systematic review and research of the exquisite Ming and Qing ancestral portraits in the academy's collection, features many collections being displayed for the first time. The content of these ancestral portraits spans various periods and types, encompassing both the typical Bochen school portraits and the atypical ones influenced by literati artists.

The portraits on display offer a glimpse into individuals adorned in plain and elegant commoner attire, officials donned in their official regalia, and accomplished women celebrated for their contributions. Capturing the essence of different eras, the portraits portray figures wearing traditional Han attire from the Ming dynasty, while also highlighting the unique characteristics of Manchu ethnic culture. This includes depictions of military officers of the Eight Banners (Manchu military-administrative organizations in the Qing dynasty) and women adorned in banner attire. The interconnected portraits, including couples and mother-son pairs, are meticulously arranged, evoking a sense of solemn reverence.

Notably, a remarkable highlight is the relatively complete set of "Prince Shuncheng Family Ancestral Portraits", spanning six generations from the seventh to the 12th Prince Shuncheng. This impressive collection includes portraits of not only the princes, but also five generations of princesses, making a total of 11 exquisite works. Beyond offering insights into the ancestral worship traditions of the Qing dynasty's royal family, it provides a fascinating glimpse into the evolving techniques and styles of ancestral portraits in northern China during that period.

The cultural traditions linked to ancestral worship, such as showing great care at the end to honor the past and the continuation of generational succession, remain unbroken. This underscores the act of worshiping ancestral portraits as a powerful expression of folk spirituality, contributing to the maintenance and strengthening of family bonds, the preservation of social stability, and the promotion of harmonious societal development.

In this exhibition, presented in three chapters, the artistic and cultural value of the Ming and Qing ancestral portraits from the collection are vividly showcased. Through this, the audience is invited to reexamine the cultural significance of family worship, allowing for a genuine reflection on traditional roots, national spirit, and familial heritage.

Whats On

Whats On  Whats On

Whats On